The Current Legislative Landscape

The Scottish Parliament Information Centre (SPICe) has set out the existing legislation that impacts upon building standards in Scotland. This is reproduced below in italics:

The Building (Scotland) Act 2003 gives Scottish Ministers the power to make building

regulations to:-

- secure the health, safety, welfare and convenience of persons in or about buildings and of others who may be affected by buildings or matters connected with buildings

- further the conservation of fuel and power

- further the achievement of sustainable development

Building standards are currently set out in the Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004; the system aims to ensure building work meets the minimum standards of design and construction set out in building regulations. The system operates in the public interest, rather than to protect theinterests of individual property owners or developers.

Scottish Building Regulations

The Building (Scotland) Regulations are made by the Scottish Ministers and subject to approval by the Scottish Parliament.

Scottish Building Standards Procedures

The Building (Procedure) (Scotland) Regulations 2004, as amended, set out the procedures to be followed in connection with the submission of applications for building warrants, completion certificates and other related matters. It allows

Scottish Ministers to appoint individuals and organisations as verifiers and certifiers.

It also grants Scottish Ministers powers to approve schemes, operated by third parties -generally construction industry professional bodies, to allow suitably qualified members to act as approved certifiers of design or construction.

Guidance on the implementation of these Regulations can be found in The Scottish Building Standards Procedural Handbook.

Technical Handbooks

Detailed technical guidance for architects, engineers and other building industry professionals on how to meet the requirements set out in building standards are provided in technical handbooks, which are published and regularly updated by the Scottish Government. There are separate handbooks for domestic and non-domestic buildings, reflecting the different requirements for each type of building. A verifier should accept a proposed design if the guidance in the technical handbooks has been followed in full, as this would indicate that the building regulations have been complied with.

While adhering to the advice in the technical handbooks is the normal way of complying with the building regulations, a designer may put forward other ways of meeting their requirements. However, the onus rests with the designer to prove to the verifier that their solution meets the required standards. This may involve testing which, due to the cost, could restrict the use of this option in some cases.

Verifiers

In Scotland all building standards verification is currently undertaken by local authorities. The Building (Scotland) Act 2003 gives Scottish Ministers the power to appoint other organisations as building standards verifiers. To date, Scottish Ministers have not appointed any organisations, other than local authorities, as building standards verifiers.

Building Warrants

Anyone wishing to erect a new building or alter, extend, convert or demolish an an existing building normally requires permission from a verifier. Permission is granted in the form of a building warrant. A verifier will grant a building warrant if the proposed work meets the requirements of the Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004, as currently amended (section 9, Building (Scotland) Act 2003). It is an offence to begin work for which a warrant is required without being granted one (section 8, Building (Scotland) Act 2003).

Completion Certificates

Once building work is complete or a building is converted, the property owner or their agent must submit a completion certificate to the verifier. A completion certificate is needed to confirm that a building has been constructed, altered or converted in accordance with the warrant and the Building (Scotland) Regulations 2004. It is an offence to submit a false completion certificate or to occupy a building without a completion certificate being accepted by the verifier (section 20, Building (Scotland) Act 2003).

Reasonable Inquiry

Verifiers are required to undertake ”reasonable inquiry” to confirm that building work complies with the details set out in the building warrant, and the requirements set out in building regulations, before accepting or rejecting a completion certificate (section 18, Building (Scotland) Act 2003). There is no statutory definition of what constitutes “reasonable inquiry,” however, it can include site visits, examination of photographic evidence and considering test reports or certificates of construction issued by an Approved Certifier of Construction.

The type and amount of any evidence gathering is a matter for the verifier. It is important to note that inspections carried out by verifiers are to protect the public interest. They do not provide assurance that building work has been carried to meet the requirements of the relevant person (usually the property owner or developer).

When submitting a completion certificate to the verifier, the relevant person is required to certify that all the completed work is in accordance with the approved building warrant and meets the requirements of building regulations. This means ultimate responsibility for compliance with building regulations lies with the relevant person.

The issue of a completion certificate by a verifier does not remove any responsibility from the relevant person.

Local Authorities Enforcement Powers

Local authorities are responsible for the enforcement of building regulations. The Building (Scotland) Act 2003 gives them formal powers to deal with work or conversions done without a building warrant when one was required. Also, where a building warrant has been obtained, powers to deal with work not done in accordance with the building warrant and building regulations. They also have powers to deal with buildings they consider to be defective or dangerous.

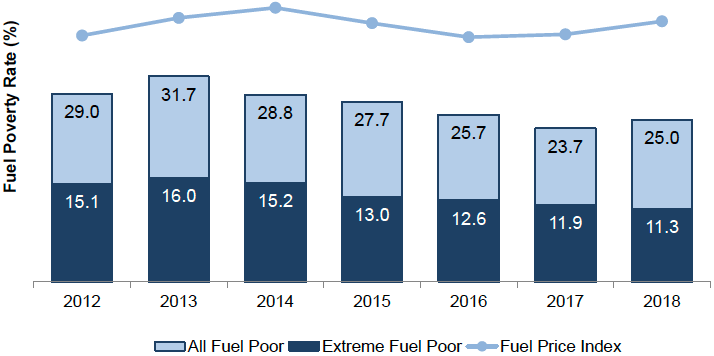

Fuel Poverty

The Scottish Government uses the following definition of fuel poverty as set out in the Fuel Poverty (Targets, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Act 2019 (the “Fuel Poverty Act”):

Definition

Section 3 of the Fuel Poverty Act establishes a new two-part definition whereby a household is considered fuel poor if:

- After housing costs have been deducted, more than 10% (20% for extreme fuel poverty) of their net income is required to pay for their reasonable fuel needs; and

- After further adjustments are made to deduct childcare costs and any benefits received for a disability or care need, their remaining income is insufficient to maintain an acceptable standard of living, defined as being at least 90% of the UK Minimum Income Standard (MIS).[1]

The Energy saving trust define extreme fuel poverty:-

‘Extreme fuel poverty is defined as requiring more than 20% of income for domestic fuel.’ An additional element to this definition was added by the Fuel Poverty (Targets, Definition and Strategy) (Scotland) Act 2019 [2] A household is in extreme fuel poverty if—

the fuel costs necessary for the home in which members of the household live to meet the conditions set out in section 3(2) are more than 20% of the household’s adjusted net income, and

after deducting such fuel costs, benefits received for a care need or disability (if any) and the household’s childcare costs (if any), the household’s remaining adjusted net income is insufficient to maintain an acceptable standard of living for members of the household.[3]

For extreme fuel poverty, the cost of meeting the household’s assessed fuel needs must amount to more than 20% of the net income that the household has after it has paid its housing costs (rather than the 10% which is required for fuel poverty). The other difference is that benefits received for a specified care need or disability are not taken out of account when considering whether a household has sufficient income left to maintain an acceptable standard of living.

Fuel Poverty is caused by a combination of factors: poor energy efficiency of a dwelling; low disposable household income, the high price of domestic fuel and how energy is used in the home.

[4]

Those living in fuel poverty disproportionately live in houses and flats that have poor levels of energy efficiency, heating systems that are more expensive to run and homes that are constructed of materials that make retrofitting more difficult. The combination of these and other factors such as overcrowding, poor maintenance by landlords and low household incomes are all factors that in any year could plunge people into fuel poverty but 2021 was exceptionally bad due to one additional and very significant pressure, the rise in energy prices.

Gas Price Rises

Over the course of this year, the sharp rise in wholesale gas prices resulted in more and more individuals and families falling into fuel poverty.

According to Energy Action Scotland, ‘an additional 150,000 people in Scotland could be forced into fuel poverty this winter (2021) due to an increase in energy prices ..energy bills are expected to rise by an average of £375 this winter compared with the previous 12 months and there has been a 12% increase in the energy price cap alone resulting in concerns that more than one million people across Scotland may be unable to afford to heat their homes adequately’.[5]

This rise in wholesale gas prices and competition between energy providers to secure customers has resulted in a crisis in the domestic market as fuel bills have reached unprecedented levels. As prices rose, customers who were on longer-term fixed price contracts found their energy provider selling gas and electricity to them for less than it cost them to buy it wholesale. This was an unsustainable position resulting in a rush of smaller but not insignificant suppliers going bust.

As companies such as Avro Energy, People’s Energy, Utility point, PFP Energy, MoneyPlus Energy, Hub Energy etc. went out of business, regulators were forced to step in to ensure customers had continuity of supply by transferring them to a new supplier at prices that met the energy cap with a consequential increase in household bills. This is a temporary fix to prevent consumers having their supply cut off but it is not a long-term solution and does little in itself to address poverty.

In February 2022 Ofgem, the UK energy regulator said, “The energy price cap will increase from 1 April for approximately 22 million customers. Those on default tariffs paying by direct debit will see an increase of £693 from £1,277 to £1,971 per year (difference due to rounding). Prepayment customers will see an increase of £708 from £1,309 to £2,017.

The increase is driven by a record rise in global gas prices over the last 6 months, with wholesale prices quadrupling in the last year.”[6]

At today’s prices electricity is around four times more expensive than gas, so by phasing out gas heating in new build housing by 2024 as proposed by the Scottish Government we risk pushing more people into fuel poverty, unless heat pump installation is coupled with significant improvements in the energy performance in our new buildings and a major retrofitting programme in older properties.

A recent report published by the Wise group advises that “24% of participants rationed or disconnected their electricity during the study period and that 56% of them did so at least once a week”.

The report went on to say “electric heating is 3-4 times more expensive than gas heating. One unit of mains gas (measured in kW/h) costs around 4p per kW/h. Conversely, one unit of electricity from the mains (also measured in kW/h) will cost 15/kWh.”

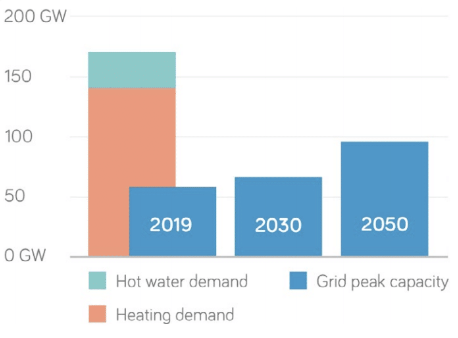

Therefore, replacing cheaper gas for heating with more expensive electricity will only work if homes are able to use that electricity in an efficient and effective way. It cannot be met by decarbonising the grid because the capacity of the grid has limits. Whilst the potential of renewable energy is very significant the capacity to harvest it is not – there is a financial and carbon cost to all renewable technology. Like fossil fuel generated energy, renewable energy and storage capacity has to be shared across all sectors 44.

Fuel poverty across the UK

The gas price crisis has significantly increased awareness of fuel poverty across the whole of the UK. The application of different methodologies to calculate fuel poverty rates in each of the different nation states makes it difficult to carry out an accurate and direct comparison of fuel poverty rates. However, the estimate from the House of Commons library dated July 2021 suggests 25% of households in Scotland were classed as fuel poor, 13% in England, 12 % in Wales and 18% in Northern Ireland.[8]

(see Appendix III)

The figure for Scotland reflects the data from the last Scottish House Condition Survey that was conducted in 2018.

Fuel poverty rates in Scotland by local authority

Na h Eileanan Siar 40%

Highland 33%

Argyll and Bute 32%

Moray 32%

Dundee 31%

Orkney 31%

Shetland 31%

Dumfries and Galloway 29%

Scottish Borders 29%

West Dunbartonshire 29%

Inverclyde 28%

North Ayrshire 28%

East Ayrshire 28%

Glasgow City 25%

Perth & Kinross

Aberdeen 24%

Clackmannanshire 24%

East Lothian 24%

Fife 24%

South Ayrshire 23%

Angus 22%

Falkirk 22%

Renfrewshire 22%

South Lanarkshire 22%

Edinburgh 21%

Stirling 21%

East Dunbartonshire 20%

North Lanarkshire 20%

Midlothian 19%

West Lothian 18%

East Renfrewshire 13%

Scotland average 24%[10]

The Scottish Government’s New Statutory Targets

The new fuel poverty statutory target (section 2 of the Fuel Poverty Act) is to ensure that, in the year 2040 as far as reasonably possible no household is in fuel poverty and :-

- No more than 5% of households in Scotland will be in fuel poverty

- No more than 1% of households will be in extreme fuel poverty

- The median fuel poverty gap of households in Scotland in fuel poverty is no more than £250 (adjusted to take account of changes in the value of money)

The Scottish Government’s Energy Efficient Scotland programme will be the primary delivery mechanism for eradicating fuel poverty by 2040.

The strategy states, ‘Our homes and workplaces account for around 21% of Scotland’s total greenhouse gas emissions. We can and must make very significant progress towards eliminating emissions from the way we heat our buildings over the next decade and reduce them to zero by 2045. Transforming our homes and workplaces will be immensely challenging, requiring action from all of us, right across society and the economy’.[11]

The strategy’s key priorities include:-

- Reducing carbon emissions

- Reducing fuel poverty

- A commitment to a ‘fabric first’ approach to reduce emissions, cut fuel bills and keep homes warm

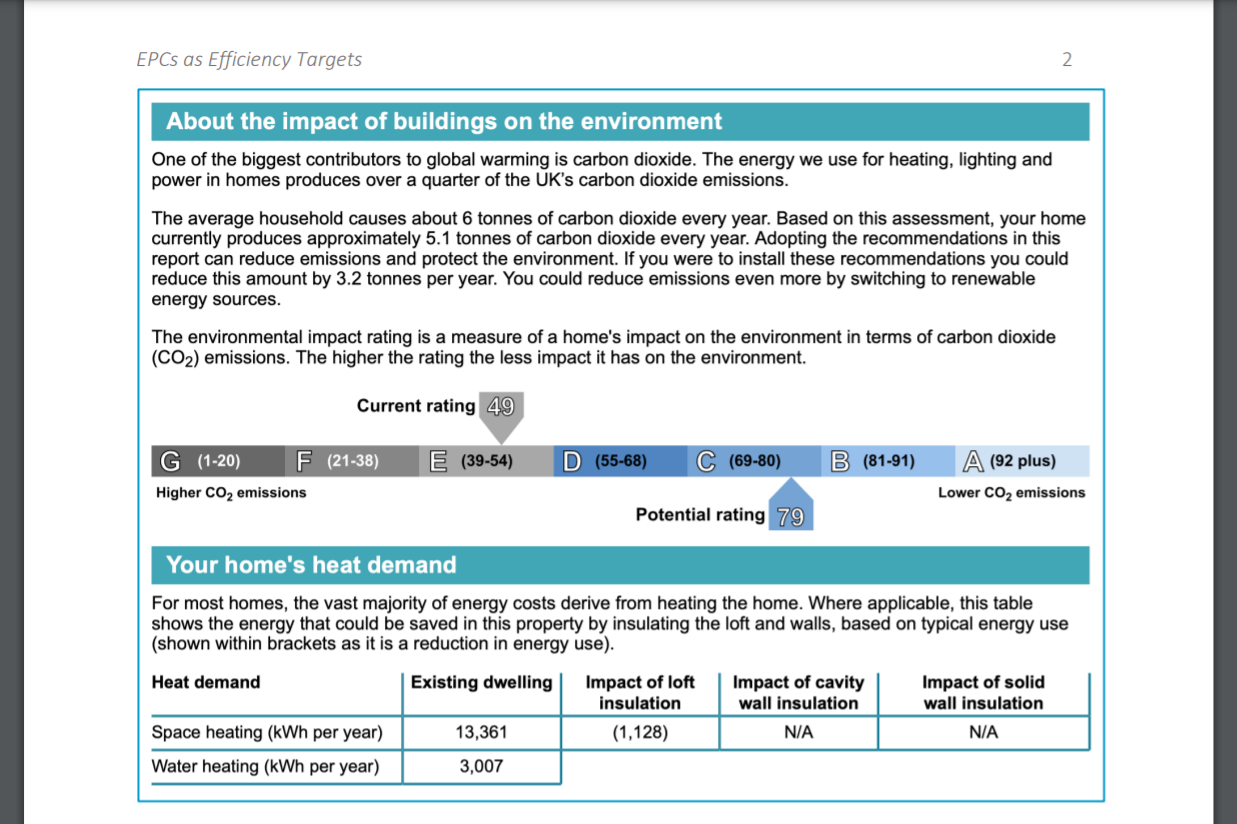

It goes on to say ‘We are therefore aiming to reach high standards of energy performance across all buildings whatever heating systems they use. For homes this will mean achieving energy efficiency levels broadly equivalent to an EPC rating of Band C’.[12]

‘Achieving emissions reductions in buildings will require by 2030 over 1 million homes and an estimated 50,000 non-domestic buildings to convert to using zero or low emissions heating systems. We are committed to taking action to rapidly scale up deployment rates so that at least 64,000 homes install renewable heating systems per year by 2025, and possibly many more.’[13]

In relation to new build housing, the strategy goes on to say :-

‘While new buildings represent only a small part of the decarbonisation challenge, we cannot add any new emissions because of the rapid decarbonisation efforts needed to reach net zero. We will require new buildings, starting with new homes consented from 2024, to use zero direct emissions heating, and also feature high levels of fabric energy efficiency to reduce overall heat demand so that they do not need to be retrofitted in the future.’[14]

‘We will continue to prioritise action on energy efficiency. To deliver regulations to support the installation of cost-effective ‘energy efficiency first’ improvements in all buildings (e.g. roof, windows, wall and floor insulation); both the retrofit of existing buildings and increased energy performance of new buildings’.[15]

Emissions for reporting against targets

The most recent Scottish Government Climate Change Plan sets out four policy outcomes for this sector, the indicators for which are summarised below:-

| The heat supply to our homes and non-domestic buildings is very substantially decarbonised, with high penetration rates of renewable and zero emissions heating. | On Track | Off Track | Too Early to Say |

| % heat in buildings from low greenhouse gas emissions sources | x | ||

| % of buildings using low greenhouse gas emission heating systems | x |

| Our homes and buildings are highly energy efficient, with all buildings upgraded where it is appropriate to do so, and new buildings achieving ultra-high levels of fabric efficiency | On Track | Off Track | Too Early to Say |

| Energy intensity of residential buildings (MWh per household) | x | ||

| Energy intensity of non-domestic buildings (GVA in the services sector per GWh) | x | ||

| % of homes with an EPC (EER, or equivalent) of at least C | x | ||

| % new homes built with a calculated space heating demand of not more than 20 kWh/m²/yrT | x |

| Our gas network supplies an increasing proportion of green gas (hydrogen and biomethane) and is made ready for a fully decarbonised gas future. | On Track | Off Track | Too Early to Say |

| % of Scottish gas demand accounted for by biomethane and hydrogen blended into the gas network | x |

| The heat transition is fair, leaving no-one behind and stimulates employment opportunities as part of the green recovery | On Track | Off Track | Too Early to Say |

| Percentage of households in fuel poverty | x |

Scottish Government Consultation on Building Standards

From July to November 2021, the Scottish Government consulted on new building regulations which could introduce changes to support the implementation of a new build heat standard from 2024. (see Appendix V)

Amongst other things, the consultation sought views on:-

● The introduction of an energy target for new buildings

Proposal – we are proposing the introduction of a further target, using calculated energy demand as the metric. This will become increasingly relevant as the decarbonisation of fuels, such as grid-supplied electricity, continues and in the context of 2024 heat standard proposals, to require new buildings to use only ‘zero direct emissions’ heat sources.[17] This in the main means replacing gas boiler fuelled heating for electricity.

● Options for uplift in standards for new dwellings

There are two specification options for overall levels of improvement set out in the consultation.

Option 1: ‘Improved’ standard:

- Notional Building 1 – Air Source Heat Pump (ASHP) + improved fabric + natural ventilation (‘ASHP improved’), where dwelling is heated by a heat pump.

- Notional Building 2 – Gas boiler + improved fabric + natural ventilation + PV (‘Gas improved’), where dwelling is heated by any other means.

- This option results in an aggregate emissions reduction of 32% over the 2015 standards assuming no significant change in fuel mix reducing heat demand by identifying improved building fabric values; glazing achievable with double glazed units; fabric infiltration of 5 m³/(m².h)@50Pa and use of intermittent extract fans with trickle vents.[18]

Option 2: ‘Advanced’ standard:

- Notional Building 1 – Air Source Heat Pump (ASHP) + advanced fabric + MVHR (‘ASHP advanced’), where dwelling is heated by a heat pump.

- Notional Building 2 – Gas boiler + advanced fabric + MVHR + PV (‘Gas advanced’), where dwelling is heated by any other means

This option results in an aggregate emissions reduction of 57% over the 2015 standards assuming no significant change in fuel mix – reducing heat demand by identifying more stringent building fabric values; glazing achievable with triple glazed units; fabric infiltration of 3 m³/(h.m²)@50Pa and use of mechanical ventilation and heat recovery.[19]

Whilst any improvements in energy efficiency, emissions reductions and improved building standards are to be welcomed, if Scotland is to meet the previously described fuel poverty and energy efficiency targets and its climate obligations then we will need to see a much more radical approach that delivers rapid change at an appropriately high standard. These changes cannot be achieved by decarbonising the grid alone as the capacity of the grid has to be shared by all sectors. Whilst we do need to take action to reduce the grid’s reliance on carbon this will not eradicate fuel poverty or meet our energy efficiency targets with additional action across all sectors. A step change is required on many fronts.

The Scottish Government proposals do not include consideration of the wholesale introduction of Passivhaus standards for all new build housing. I consider that the level of change being considered in the options set out by the Government will not make sufficient progress towards eradicating fuel poverty or meeting our efficiency targets. I believe that legislation is required to change standards to make a far bigger contribution towards these aims and that is why I am proposing regulations specifically to deliver Passivhaus standards.

The Performance Gap

The concern of those campaigning for improved standards of energy efficiency in new build homes is the extent of the gap between what is expected to be achieved under the current Scottish building standards and what is actually delivered – this is referred to as ‘the performance gap’.

On this the zero carbon hub say,

‘In recent years, the housebuilding industry and government have grown increasingly concerned over the potential gap between design and ‘as-built’ energy performance. It could undermine a building’s vital role in delivering the national carbon reduction plan, present a reputational risk to the housebuilding industry and damage consumer confidence if energy bills are higher than anticipated.’[20]

When someone buys a new home constructed under the current building regulations the developer will provide:-

– A building control completion certificate which is mostly evidenced by signed certificate from the client or contractor (known as the relevant person)

– Planning conditions discharged

– A structural warranty (NHBC or similar)

– Health and safety file which includes as built drawings, manufacturers information etc

– An Energy Performance Certificate displayed in the house

Other than that there is little consumer protection regarding the performance of homes other than challenging and proving negligence against part of the development team in the courts.

Council Building Control Departments are often incorrectly perceived to perform a a quality control function but this is not the case as responsibility for compliance remains with the builder. The energy rating of a property is a theoretical estimate of how different house types and designs perform in relation to energy efficiency. It is not based on an actual individual and verificable assessment of each new build dwelling. The performance gap is the gap between what level the housebuilder claims the house will perform to as per the ESPC rating and what is actually delivered. Studies suggest this can be as much as 60%.The zero carbon hub says, ‘Verification by Standards Assessment Procedure (SAP) assessor accreditation bodies currently tends to focus on the calculation procedures themselves rather than a more intensive audit of the information provided at the design and construction phase. This means the differences between the design intent and actual built specification are potentially missed, even though an ‘as built’ SAP assessment is required by building regulations.’[21]

So, whilst any new build home requires a completion certificate and Energy Performance Certificate from the local authority they do not require a home report or any verification or independently certified assurance that their new home will perform to the standard claimed.

‘The common perception that improving EPC ratings can drive lowering emissions but this is unlikely to work in practice. The reasons for this are 1) It uses a notional building technique 2) The assessment model sets a minimum standard for fabric elements but these are backstop values designed to prevent poor practice rather than encourage good fabric values and critically, the Dwelling Emission Rate and EPC rating includes the offsetting effect of any photovoltaic panels and so you can achieve a very high EPC rating on a dwelling with an average fabric performance by adding a modest amount of PV generation. However, the problem is that the emission rate associated with electricity is reducing due to more renewables at national level and is already lower than gas. As this reduces further, the emissions associated with a dwelling which uses gas (e.g. for heating and hot water) will far outweigh the emissions saving from generating electricity. This will be reflected in the environmental impact rating shown on the EPC, but, as mentioned earlier, this is rarely used and is not placed prominently on the EPC. Finally, the EPC rating itself is a cost-based index – i.e. the final score is linked to how much the type of energy used costs. As gas is (and is likely to remain) far cheaper than electricity, a dwelling that uses electricity in preference to gas for heating will be penalised. However, as set out above, with the emissions rate for electricity dropping, an electric-based dwelling will result in a lower rate of emissions.’[23]

John Gilbert architect confirmed this, “There are very few consumer protection laws around new housing and ensuring quality construction is a bit of a lottery for new home buyers.”

Conversely, evidence of meeting the Passivhaus standard is audited by an independent external body to ensure it meets the Passivhaus standard. This evidence would in turn be submitted to a local authority building control department as part of the completion certificate process. There should be no performance gap in an accredited Passivhaus building. A project to examine the performance gap in new build homes has been undertaken by the zero carbon hub. It has brought together 140 industry experts from 90 companies to identify areas that need to be addressed if the performance gap is to be eradicated.

In their interim progress report, Closing the gap between design and as-built performance[24]they say:-

‘There is a general lack of understanding across developers, designers and planners about the potential impact they can have on energy performance and buildability.’’[25]

The report goes on to highlight:-

- The need to improve communications, share information and good practice at an early stage in the design process

- The lack of a robust energy performance tool

- The need for products and materials to be tested for energy performance not in isolation, as individual components, but as systems or fabric assemblies constructed on site

- The need to robustly assess actual ‘as built’ performance of substitute or equivalent products as opposed to assumed performance

- The problems associated with the adoption of improvised or ‘ad-hoc’ approaches being used on site without understanding energy performance implications

- How, aesthetically driven features, such as dormers and bays, can create complexity for both the detailed design and construction stages.

- That a focus on design process energy efficiency calculation procedures means the differences between the design intent and actual built specification are potentially missed

- That there should be a review of thermal bridge calculations

- That knowledge, skills and working practices within the industry are a serious concern and will have an influence on both the performance gap and the ability to close it

The involvement of so many players within the industry and the seriousness with which they are taking the issue of the performance gap shows it is a significant issue.

Closing the performance gap

To address and eradicate the performance gap this bill would see the Passivhaus Planning Package (PHPP), an energy efficiency planning tool used by architects and planning experts, adopted into building standards as an alternative means of compliance. This would complement the development of any Scottish Passivhaus equivalent which would not require Passivhaus certification. However, both Passivhaus certification or an equivalent standard would be signed off by the relevant local authority building control department. In a similar way to current practice but with a higher threshold of evidence.

[1] https://www.gov.scot/policies/home-energy-and-fuel-poverty/fuel-poverty/

[2] https://www.gov.scot/policies/home-energy-and-fuel-poverty/fuel-poverty/

[3] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2019/10/section/4

[4] Causes of energy poverty [2] | Download Scientific Diagram (researchgate.net)

[5] Energy crisis and price cap rise ‘could force 150,000 more Scots into fuel poverty’ – Scottish Housing News

[6] Price cap to increase by £693 from April | Ofgem

[7] UK Passivhaus Trust graph, data collected from

(i) -Decarbonising domestic heating: What is the peak GB demand?, Watson et al, ScienceDirect.com, March 2019

(ii)- www.nationalgrideso.com/future-energy/future-energy-scenarios/fes-2020-documents

(iii)-UK housing: Fit for the future?

[8] https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-8730/CBP-8730.pdf

[9] Scottish house condition survey: 2018 key findings – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[10] https://www.dailyrecord.co.uk/news/politics/fuel-poverty-scotland-laid-bare-25818155

[11] Heat in buildings strategy – achieving net zero emissions: consultation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[12] Heat in buildings strategy – achieving net zero emissions: consultation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[13] Heat in buildings strategy – achieving net zero emissions: consultation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[14] Heat in buildings strategy – achieving net zero emissions: consultation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[15] Heat in buildings strategy – achieving net zero emissions: consultation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[18] Building regulations – energy standards and associated topics – proposed changes: consultation – gov.scot (www.gov.scot)

[19] Building regulations – energy standards and associated topics – proposed changes: consultation – goGuidance (passivhaustrust.org.uk)v.scot (www.gov.scot)

[20] Performance Gap | Zero Carbon Hub

[21] Performance Gap | Zero Carbon Hub

[22] https://www.passivhaustrust.org.uk/UserFiles/File/research%20papers/EPCs/2020.04.17-EPCs%20as%20efficiency%20targets-v9.pdf

[23]EPCs as Efficiency Targets

[24] Closing the Gap between Design & As-Built Performance (zerocarbonhub.org)

[25]https://www.zerocarbonhub.org/sites/default/files/resources/reports/Closing_the_Gap_Between_Design_and_As-Built_Performance-Evidence_Review_Report_0.pdf