Budget 2020/21: Finance Committee Briefing on Fiscal Framework

Headlines

- Resource spending in the 2020/21 budget is up almost 5% in real terms compared to the 2019/20 budget (excluding new resources for social security and changes to the accounting for farm payments, post-Brexit).

- The increase is entirely due to increases in the Barnett-determined block grant.

- The ‘net tax’ position – the difference between Scottish revenues and the BGAs – is forecast to contribute £160m in total to the resource budget in 2020/21.

- Tax reconciliations to reflect forecast error in previous years imply a downward adjustment to the 2020/21 budget of £207m. But rather than reduce its 2020/21 spending by £207m, the Scottish Government has chosen to use its borrowing powers. The government will repay the forecast error over the next five years, rather than letting spending in 2020/21 take the ‘hit’.

- Since December 2018, the SFC has revised up its forecast of Scottish earnings growth in all years of the forecast. However, for 2018/19, the positive impact of these upward revisions to earnings forecasts on income tax revenues has been offset by various other adjustments which serve to reduce the forecast for Scottish income tax revenues. As a result, the forecast tax ‘reconciliation’ for 18/19 is currently forecast at £555m – down since May 2019 but up since December 2018.

- For 2019/20 and 2020/21, the upward revisions to forecasts of Scottish earnings growth and Scottish income tax revenues are more than offset by larger upward revisions to the forecasts of rUK income tax revenues and hence the BGA. Thus the difference between Scottish revenues and the BGA is forecast to be just £46m in 2020/21, despite the implementation of a Scottish tax policy that raises over £600m in additional revenues compared to the UK policy.

- In other words, if it were not for the Scottish income tax policy, income tax revenues are likely to be around £600m lower than the BGA.

- In 2020/21, spending on social security payments in Scotland is forecast to be broadly in line with the increase in the block grant that coincides with their transfer. However the Scottish Government’s policies in relation to the Carer’s Allowance Supplement, the Income Supplement and the Disability Assistance for Children and Young People (DACYP) are forecast to be associated with additional costs. Future budgets will be exposed to the risk that spending on social security payments in Scotland exceeds the increase in the block grant, and that spending is higher than forecast.

| Summary of income tax issues Summary of income tax issues: 2018/19 In 2018/19, if the Scottish tax base (notably earnings) had grown at the same rate as rUK, we might expect that Scottish revenues would be over £400m higher than the BGA. This is indeed what was forecast at the time of the 2018/19 budget, which forecast a ‘net tax’ position of £428m. The SFC is now forecasting Scottish earnings to grow more quickly than it was when it prepared the budget 2018/19 forecasts. But tax revenues have not grown quite as quickly as anticipated due to various other data and policy issues. At the same time, rUK tax revenues have grown markedly faster than the OBR had forecast in November 2017, more than offsetting the improvement in the Scottish outlook. The latest forecast for the ‘net tax’ position in 2018/19 is -£127m, implying a potential reconciliation of -£555m on the basis of latest forecasts. Summary of income tax issues: 2019/20 Since December 2018 the SFC has revised up its forecast of earnings growth, but this has been offset by some other data issues (including weaker employment growth and weaker than anticipated outturn for 17/18). Taken together this results in a slight deterioration in the Scottish forecast and a slight worsening in the net tax position. Summary of income tax issues: 2020/21 Compared to December 2018 the SFC has revised up its forecast of earnings growth, and has revised up its forecast of Scottish tax revenues by £80m. But the forecast of the BGA has increased by over £200m, resulting in a deterioration in the forecast net tax position. If the Scottish earnings growth had matched rUK, we might expect Scottish revenues to be over £600m more than the BGA[1]. But the latest forecasts imply it will be £46m higher than the BGA. |

1. Economic forecasts

The forecast for GDP growth has been revised down slightly for 2019 (from 1.2 to 0.9 per cent) but revised up very marginally in 2021 and 2022. The SFC notes that whilst there has been some ‘unwinding’ of Brexit-related uncertainty, Brexit remains a risk to economic growth, particularly given uncertainty over the nature of the future economic relationship with the EU.

Nonetheless, Brexit is not the only factor underpinning a subdued outlook. The forecast for productivity growth has again been revised down, and slowing global growth is also material. These structural risks are at least as important as Brexit in determining the subdued outlook.

On a more positive note, forecasts for earnings growth have been revised up since this time last year, reflecting recent outturn data for earnings. The implication of the earnings data is discussed subsequently.

Differences in

forecasts of GDP per capita and average earnings growth between the OBR (for

UK) and SFC for Scotland in 2020 and beyond are very slight (Table 1).

Table 1: Comparison of growth forecasts, SFC for Scotland (Feb 2020) with OBR for UK (March 2019)

| 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||

| GDP | OBR Mar-2019 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| SFC Feb-2020 | 1.5 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 1.2 | |

| GDP per person | OBR Mar-2019 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| SFC Feb-2020 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 1.0 | |

| Average annual earnings | OBR Mar-2019 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.1 |

| SFC Feb-2020 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.2 |

2. IT forecasts and net tax position

How have the income tax forecasts changed since last year?

There have been two main developments:

- Outturn income tax for 17/18 was £92m lower than forecast, which causes SFC to revise down its forecasts for future years.

- But offsetting this, earnings growth has been stronger than forecast during 2018 and 2019. This causes the SFC to revise up its forecasts for 2018/19 and subsequent years.

The interaction of these two offsetting effects, together with some other developments[2], mean that income tax forecasts have been revised down in 2018/19 and 2019/20, but revised up in 2020/21 and subsequent years (Table 2).

Table 2: Income tax forecasts at successive budget events (£ million)

| 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | |

| Budget 2017/18 | 11,857 | 12,320 | 12,943 | 13,681 | 14,595 |

| Budget 2018/19 | 11584 | 12177 | 12647 | 13152 | 13733 |

| Budget 2019/20 | 11,008 | 11,452 | 11,684 | 12,285 | 12,746 |

| Budget 2020/21 | 10,916 | 11,378 | 11,677 | 12,365 | 12,897 |

| Change, 19/20 – 20/21 | -92 | -74 | -7 | 80 | 151 |

How has income tax policy changed, and what are the revenue effects?

In 2020/21, the Higher Rate and Top Rate thresholds will be frozen in cash terms, whilst the thresholds at which Scottish taxpayers begin to pay the basic and intermediate rates will increase slightly (but not by as much as inflation).

There is the potential for some confusion around what is happening to the basic and intermediate rate thresholds. Most people would probably interpret the Budget Statement as meaning that the thresholds at which taxpayers pay these thresholds will increase by inflation.

However, what the government is doing is increasing the size of the relevant band by inflation. In the case of the basic rate, the government is not increasing the threshold from £14,549 by 2 per cent. Instead it is increasing the difference between £14,549 and the Personal Allowance (£12,500) by 2 per cent.

This means that the threshold at which Scottish taxpayers move out of the starter rate and onto the basic rate is increasing by less than inflation. The advantage of stating the policy this way is that, if the UK Government increases the Personal Allowance on 11 March, the starter rate band in Scotland will maintain an equivalent ‘distance’ to the Personal Allowance.

The government will argue (justifiably) that this way of uprating thresholds is consistent with how the UK Government uprates the Higher Rate threshold, but it is not how most people would have interpreted the Budget Statement.

The SFC forecasts Scottish income tax revenues on the basis of the stated thresholds. However it only considers the cash freeze in the Higher Rate threshold to represent a ‘policy change’ and thus worthy of a policy costing.

The changes to the basic and intermediate bands are deemed not to represent policy change (as the size of the band is increasing in line with inflation), whilst the cash freeze to the Additional Rate is also deemed not to represent policy change on the grounds that this threshold has been unchanged since the rate was introduced by the UK Government in 2010.

To an extent however, this classification of the Higher Rate threshold freeze as a policy costing is immaterial. What matters for the Scottish budget is the difference between revenues raised in Scotland and the BGA. The provisional BGA which informs the Scottish budget 2020/21 is based on an assumption that the UK Higher Rate threshold is frozen. Thus although the freeze in the Scottish threshold is forecast by the SFC to raise an additional £49m (compared to increasing it in line with inflation), it is not revenue generating in the sense that it does not increase revenues relative to the BGA.

What are the implications for net tax position in 2020/21?

What matters for the budget is the difference between Scottish income tax revenues and the income tax block grant adjustment (BGA). The evolution of the so-called ‘net tax’ position across different budget events in shown in Table 2.

In Budget

2019/20, the net tax position was forecast to be £183m in 19/20 and £196m in

20/21. In this year’s budget, the net tax position has deteriorated to -£28m

and £46m respectively.

Table 2: Forecasts of the net income tax position at successive budgets (£ million)

| 2017/18 | 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | |

| Budget 2017/18 | 107 | 161 | 271 | 448 | 697 | |

| Budget 2018/19 | 61 | 428 | 591 | 675 | 797 | |

| Budget 2019/20 | -38 | -43 | 183 | 196 | 268 | 288 |

| Budget 2020/21 | -97 | -127 | -28 | 46 | 155 | 253 |

Note: shaded figure represents outturn

There is what might appear to be a puzzle here. If the SFC – as noted above – has revised down its Scottish income tax forecast by just £7m in 19/20, and increased the forecast for 20/21 by £80m, how come the net tax position has deteriorated in both years since December 2018?

The answer is that despite an improvement in forecast Scottish revenues for 20/21 compared to last year, the outlook for rUK income tax revenues has improved proportionately more. Hence the forecast for the income tax BGA has increased more rapidly than the forecast for Scottish revenues. This is discussed further below.

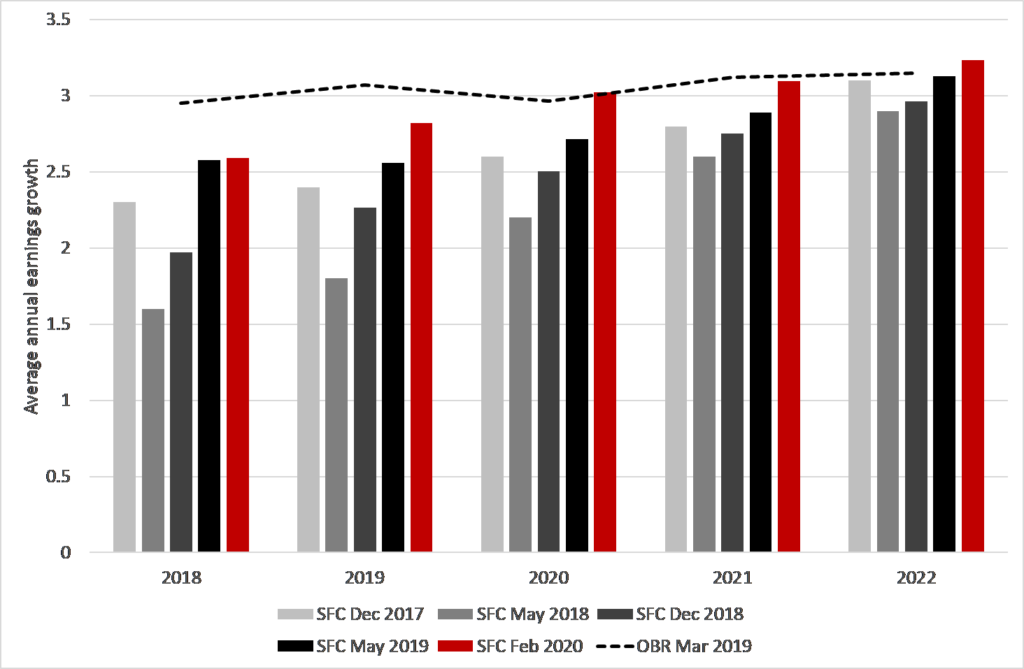

How have the forecasts of earnings growth changed?

As might have been anticipated given recent data, the SFC has revised up its forecasts of average earnings growth for each year of the forecast period.

Earnings growth is now forecast to be higher each year than it was in December 2017, and much higher than it was in May 2018 – Figure 1. (Recall that the forecast for earnings growth in December 2017 that underpinned the 18/19 Budget was substantially revised down in May 2018… the forecast has been revised up at each subsequent forecast event, and now exceeds the original December 2017 forecast).

Despite these upward revisions to the forecasts of Scottish earnings growth, it remains the case that average earnings grew less quickly in Scotland than in rUK in 2017 and 2018, and this trend is forecast to continue in 2019. This largely explains why Scottish income tax revenues are forecast to be below the BGA in those years, despite the different tax policy in Scotland.

The latest

forecasts imply that Scottish earnings growth will match UK earnings growth in

2020. But the effect of relatively weaker earnings growth in Scotland between

2017-19 will continue to be felt on the budget in future years. Even if

Scottish and rUK revenues per capita grow at the same rates from 2020 onwards, this

will merely maintain the proportionate size of the existing gap between

Scottish revenues and the BGA, rather than helping to close it.

Figure 1: Evolution of SFC earnings forecasts

| Box 1: The distribution of earnings growth In response to a recommendation of the FCC, the SFC includes some analysis of the extent to which earnings have grown at different rates in different parts of the income distribution. Two limitations of the analysis can be pointed out: First, it looks at the period 2003 – 2019 as a whole. Looking at the same data for the past 5 years tells a different picture, with incomes growing faster at the 30th percentile (3.2% per annum) than at the 90th percentile (2.1% per annum).Second, it focusses on growth in employee earnings, rather than on taxpayer NSND incomes (the latter include income from self-employment, pensions, and property). |

What are the implications for the net tax position in 18/19 and scope for ‘reconciliation’?

The forecast of the size of the income tax reconciliation in respect of 2018/19 is £550m, down slightly from the £608m that was being forecast in May (although higher than the £471m that was forecast at the time of the 19/20 Budget).

But the analysis of changes in earnings forecasts poses an interesting question. The potential for a large reconciliation in respect of 18/19 was first raised in May 2018 when the SFC significantly revised down its earnings forecasts. But if the latest forecasts imply earnings growth higher than the December 2017 forecasts (which informed the 18/19 budget), why is there still a significant reconciliation being forecast?

The answer – in essence – is that the OBR has revised up its forecasts of rUK income tax revenues quite significantly. Its November 2017 Forecast implied that rUK revenues would grow 2.2% between 16/17 and 18/19, but its latest forecasts imply that rUK revenues will grow 5.1% over those two years.

At the same time however there has been some downward revision to the forecast growth of Scottish income tax revenues since December 2017 (despite the improvement in outlook for earnings growth – which emphasises that the correlation between earnings growth and tax revenue growth is not perfect, and is influenced by other factors too). The SFC’s December 2017 forecasts implied Scottish tax revenues would grow 5.1% between 16/17 and 18/19, whereas the latest forecasts imply growth of 4.2% over this period.

To summarise, the forecast reconciliation of £555m for 18/19 can largely be explained by upwards revisions to the OBR forecasts for rUK income tax revenues, although less significant downwards revisions to the SFC forecasts seem also to have played a role.

How might the UK budget on 11 March change the picture?

The UK Budget will see the OBR revise its forecasts for UK income tax, and these will impact the forecast BGAs. The UK Government may also change rUK income tax policy.

First, consider the implications of a change to OBR rUK income tax forecasts (that do not result from any changes in UKG tax policy).

- If the OBR revises up its forecasts for rUK income tax revenues in 2020/21, this will ultimately result in an upward revision to the forecast income tax BGA – and hence a deterioration in the net tax position[3]. However, the Scottish Government is under no obligation to alter the spending plans set out in its 2020/21 budget. Under the terms of the Fiscal Framework, the BGAs that informed the Budget can be ‘locked in’ until outturn data is available and reconciliation takes place.

- If the OBR revises down its forecasts for rUK income tax revenues, this will ultimately result in a downward revision to the size of the BGAs. Under the agreement reached between the Scottish and UK Governments in the lead up to the budget, the Scottish Government could under this circumstance choose to ‘take’ any improvement in the net tax position in this year’s budget – resulting in a budget ‘boost’ at autumn budget revisions.

Therefore the Scottish Government has some flexibility as to whether to deal with changes to BGA forecasts on 11 March during the 2020/21 financial year, or wait until outturn data and deal with it at the reconciliation stage (in 2023/24).

Note however that if the Scottish Government decides to use the revised income tax BGAs published on 11 March to inform its 2020/21 spending plans, it also has to use the revised BGAs for LBTT and landfill tax. It could not in other words decide to let a lower income tax BGA on 11 March inform its 2020/21 plans but simultaneously choose to stick with the BGAs for LBTT and landfill tax that have already informed its draft budget.

If the UK Government changes rUK income tax policy on 11 March, then the implication in terms of revenue effects on BGAs is the same as it is in relation to tax forecasts – the Scottish Government can choose whether to deal with changes to BGAs in 2020/21 or wait until outturn.

Note that an increase in the UK Personal Allowance would reduce the forecast of Scottish tax revenues. It would also be expected to reduce the BGA by a roughly similar amount. So the net difference would likely be small – and changes would not necessarily have to be accommodated in the 2020/21 financial year.

3. The total net tax position – including LBTT and landfill tax

Table 3 shows the net tax position for income tax, LBTT and landfill tax at three successive budget events (these are not ‘latest forecasts’ – these show the position when budgets were set).

- The total net tax position has declined at each of the last two budgets, reflecting what has happened in relation to income tax.

- LBTT is forecast to contribute a positive net tax position in 19/20 and 20/21. This largely reflects the higher rates of LBTT (including the higher rate for the Additional Dwelling Supplement) compared to the equivalent tax in England.

- Landfill tax is also forecast to contribute positively to the net tax position. This is largely due to slower than hoped for progress on banning biodegradeable municipal waste, and delays in incinerator capacity (tax policy on landfill tax is identical north and south of the border).

Table 3: Net tax position at successive budget events (£ million)

| 2018/19 | 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | |

| Income tax | 428 | 183 | 46 | 155 |

| LBTT | -12 | 76 | 85 | 69 |

| SfLT | 12 | 13 | 29 | 25 |

| Total | 428 | 272 | 160 | 249 |

4. Social Security

As discussed at the Committee’s meeting on 5th February, the transfer of financial responsibility for spending on social security payments creates two types of risk for the Scottish budget:

- One is the risk that spending on these payments is higher than the value of additional resources transferred.

- Second is the risk of forecast error, i.e. that ‘net spending’ (the difference between spending and the additional grant transferred) is higher than forecast.

In terms of the six social security payments for which there will be a ‘block grant adjustment’ the SFC’s forecasts imply that total Scottish spending in 2020/21 will, to all intents and purposes, be the same as the addition to the block grant (spending of £3.213bn versus BGA of £3.203bn).

Clearly the risk here is that the difference between outturn spending and the BGAs ends up higher than this, but at this point we have no reason to believe that the downside risk is more or less likely than the upside risk.

Note that this forecast difference between spending and BGAs does not include the Carers Allowance Supplement which is forecast to cost £39m in 2020/21.

It is also worth noting that whilst ‘Scottish versions’ of five of these six payments will not commence until after 2020/21, Disability Assistance for Children and Young People (DACYP) – which will eventually replace Disability Living Allowance for Children in Scotland – will open to new applications in summer 2020. The SFC believes that policy differences between DACYP and DLA will lead to an increase in spending relative to the relevant BGA. This increase amounts to an additional £6m in 20/, rising to over £20m in later years of the forecast.

The SFC also costs the government’s commitment to a new Income Supplement for low income families with children. This amounts to £21m in 20/21, rising to £160m by 24/25 when it will be fully rolled out.

5. Reconciliation and resource borrowing

As was known in advance, the Scottish budget faced a £204m ‘reconciliation’ in respect of 2017/18 income tax revenues: the 2017/18 budget was planned on an assumption that revenues would exceed the BGA by £107m, but in fact revenues ended up £97m lower than the BGA.

Additionally, there was a further £3m reconciliation in respect of 2018/19 LBTT and landfill tax revenues.

The Scottish Government chose to deal with these reconciliation by using its resource borrowing powers for the first time. The borrowing will be repaid over a five year period, although it is not entirely clear when repayments will fall due and what rate of interest will be charged.

6. Scotland Reserve

The Scotland Reserve is covered in detail in the SPICe briefing.

In terms of resource spending, the government anticipates a balance in the Reserve at the end of 19/20 of £206m. Spending plans in the 2020/21 budget are supported by drawdown of £100m, leaving £100m available.

The amount in

the Reserve will increase if there are underspends during the 2020/21 financial

year or if additional consequentials flow to the Scottish budget following the

UK Budget. To the extent that it can only drawdown a maximum of £250m in any

year, the government may therefore argue that it is operating the Reserve

prudently. On the other hand, the SFC points out the risks of not building up

the Reserve in the face of a potentially large income tax reconciliation

impacting the 2021/22 budget.

[1] We will never know with certainty, even once we have outturn data, how much would have been raised in Scotland had the UK policy been followed (largely because we will not know whether and how behaviours might have been different). But we will be able to estimate with reasonable certainty what the direct effects of following the UK policy would be.

[2] These other developments include changes to UK policy measures which reduce the 2020/21 forecast by £120m, although it is not clear what these include.

[3] Such a deterioration in the net tax position may or may not be offset by an increase in Barnett consequentials